what to expect when going for occipital nerve stimulator implantation

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

A half-dozen twelvemonth retrospective review of occipital nerve stimulation practice - controversies and challenges of an emerging technique for treating refractory headache syndromes

The Journal of Headache and Pain volume 14, Commodity number:67 (2013) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

A retrospective review of patients treated with Occipital Nerve Stimulation (ONS) at 2 large 3rd referral centres has been audited in lodge to optimise future treatment pathways.

Methods

Patient's medical records were retrospectively reviewed, and each patient was contacted past a trained headache expert to confirm clinical diagnosis and system efficacy. Results were compared to reported outcomes in current literature on ONS for primary headaches.

Results

Twenty-five patients underwent a trial of ONS between Jan 2007 and December 2012, and 23 patients went on to have permanent implantation of ONS. All 23 patients reached i-year follow/up, and 14 of them (61%) exceeded two years of follow-upwardly. Seventeen of the 23 had refractory chronic migraine (rCM), and three refractory occipital neuralgia (ON). 11 of the 19 rCM patients had been referred with an wrong headache diagnosis. 9 of the rCM patients (53%) reported 50% or more reduction in headache hurting intensity and or frequency at long term follow-up (11–77 months). All three ON patients reported more than fifty% reduction in pain intensity and/or frequency at 28–31 months. Ten (43%) subjects underwent surgical revision after an boilerplate of 11 ± 7 months from permanent implantation - in 90% of cases due to lead bug. Seven patients attended a specifically designed, multi-disciplinary, two-week pre-implant programme and showed improved scores across all measured psychological and functional parameters contained of response to subsequent ONS.

Conclusions

Our retrospective review: ane) confirms the long-term ONS success rate in refractory chronic headaches, consistent with previously published studies; 2) suggests that some headaches types may respond better to ONS than others (ON vs CM); three) calls into question the role of trial stimulation in ONS; 4) confirms the high rate of complications related to the equipment not originally designed for ONS; 5) emphasises the demand for specialist multidisciplinary care in these patients.

Groundwork

Chronic Daily Headache (CDH) is an umbrella term for headache disorders with a high rate of reoccurrence (15 or more days per month for 3 consecutive months). CDH represents a major worldwide wellness trouble as affects 3–v% of adults [1–3] who feel substantial disability.

Chronic migraine (CM), the most prevalent form of CDH, is divers as headache occurring more than than 15 days/month for at least 3 consecutive months, with headache having the clinical features of migraine without aureola for at least 8 days per month [four]. Recently published results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study (AMPP) institute the prevalence of CM in the U.s.a. is approximately one% [5]. The World Health System recognizes migraine as a major public health trouble, ranking information technology at seventh place among all worldwide diseases leading to disability [6]. Compared to episodic migraine, CM is associated with higher inability, inferior quality of life and greater health resource utilization [7].

Despite substantial advances in migraine therapy [8], some individuals with chronic migraine are either resistant or intolerant to guideline-based treatments [ix]. This subset of patients requires the development of farther treatments and in recent years peripheral neuromodulation, in the form of occipital nerve stimulation (ONS), has emerged every bit an selection for this subset of patients [8, x]. Several published minor retrospective studies reported promising safety and efficacy data for ONS in primary headaches.

Open label studies in trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias have shown significant, long-term benefit in 67% of refractory chronic cluster headache patients [x] and in 89% of refractory SUNCT and SUNA (brusque-lasting neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing/autonomic symptoms) patients [11]. Encouraging results in refractory chronic migraine patients led to iii, commercially funded, multi-centre randomized trials [12, 13]. The benefits shown in these trials were less dramatic than hoped for, however the studies have been criticised for methodological weaknesses, unmitigated placebo effect, and a loftier charge per unit of surgical complications, which may have obscured the full benign effect of ONS. Limited data on relevant endpoints was available at the time of studies' pattern and poor endpoint choice may have masked the truthful efficacy of ONS [13].

Thus, the literature leaves many questions unanswered about the role for ONS in chronic daily headache. Our institutions are large, third neuromodulation centers with a special interest in headaches. We agreed to pool resources and retrospectively audit our own information on ONS for CDH to help guide us on time to come clinical indications for ONS, place areas for improved clinical practice, technical do and information collection.

This newspaper reports the results of our audit and relates these to the literature. We discuss the importance of specialists within a multidisciplinary handling squad, question the use of temporary trials to select ONS-responders, and look at surgical strategies to limit hardware-related complications.

Methods

Ii large third neuromodulation centers (Guy's & St Thomas NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom and Sapienza University at Sant'Andrea Infirmary, Rome, Italy) retrospectively audited outcomes of patients receiving ONS from the previous 6 years. The audit results were analyzed with reference to available literature on ONS for CDH. Ethics committee blessing was not required for this audit.

Inspect process

All patients receiving a trial of ONS in the last 6 years at both institutions were included in the inspect. Patient demographics, headache phenotype and technical details of the surgical process(s) were nerveless from patient medical records. Telephone reviews (up to three per patient) were performed by one headache specialist for each site (GL and PM) to ostend data accuracy, system efficacy and, when needed, to re-code patients' diagnosis according to the ICHD-Ii classification [xiv].

ONS indication

At both sites, the indication for ONS was refractory chronic headaches. Patients had failed to significantly improve later adequate trials of four classes of preventive medicines and three classes of acute drugs with established efficacy [15].

ONS candidates were advised non to proceed with surgery when psychological evaluation identified conditions which could be aggravated by the treatment or cause confusion in interpreting clinical results (including, but not express to, intractable epilepsy, active major depression, psychosis, somatoform disorder, severe personality disorder).

Surgical procedure

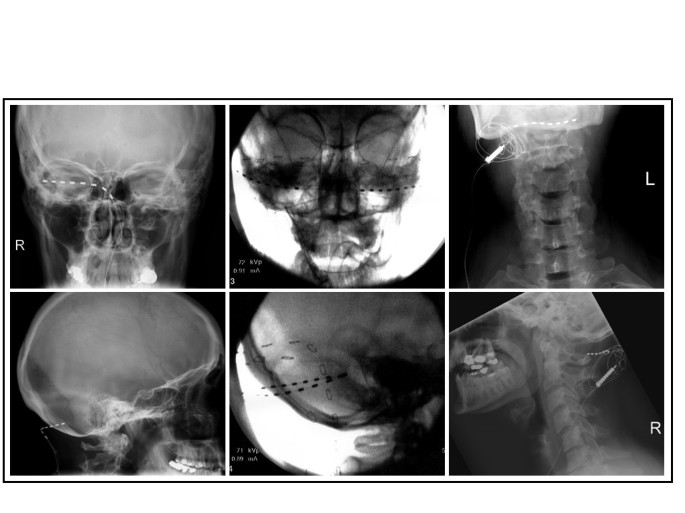

The ONS surgical procedure was performed by four different operators, with equipment and surgical technique (particularly atomic number 82 insertion and anchoring) varying between operators and over time (Figure 1). All patients underwent a trial of therapy. One or ii percutaneous lead(s) were inserted under sedation in the subcutaneous tissue to a higher place the peripheral branches of the occipital nerves at approximately C1 level, and left in place for 7 – 10 days to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of the treatment earlier beingness removed. If the trial was "successful", i.e. the patient reported at least l% decrease in headache intensity and/or frequency associated with a decrease headache medication apply, a permanent implant was then performed under full general anaesthesia. Leads were implanted as in the trial, but this time they were anchored to fascia, tunnelled, and connected to an IPG sited in a subcutaneous abdominal pocket. The exercise of leaving stress relief loops in each of the subcutaneous incisions was implemented in some of the subjects implanted after the technique was widely published equally part of large multi-centre study [16].

Example of 3 different approaches for ONS. From left to correct, i) single lead monolateral ONS; 2) dual atomic number 82, bilateral ONS; 3) single pb bilateral ONS.

Effect

The patients were treated by unlike physicians in unlike centres across a 6-year timeframe and a variety of outcomes were measured for both trial and full implant efficacy. To homogenously evaluate ONS outcomes and be consistent in neuromodulation trial evaluation, we decided a patient implanted with a permanent ONS organization would be considered a "success" if a sustained subtract of at least 50% in headache intensity and/or frequency was reported by the patient during the telephone review. Those patients with whom we did not make telephone contact were excluded from the outcome analysis regardless of the information reported in their medical notes.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) based implant preparation

In ane of the two centres involved in the study (GSTT), some patients were required to attend a pre-implant plan (PIP) earlier proceeding to the trial stage. The PIP involves groups of upwardly to eleven patients engaging in 7–9 days activity spread over 2 weeks. Physicians, psychologists, physiotherapists, nurses and occupational therapists provide a variety of broadly CBT based interventions, which explicitly seek to reduce emotional distress [17] and improve social and physical functioning [18]. This is done by addressing an individual's interpretation, evaluations and beliefs about their health condition [19].

Several outcome measures are routinely collected during the course of the PIP, many of those reflecting the IMMPACT recommendations [xx] and measuring pain-related inability as a principal outcome variable. Among those: ane) The Pain Disability Index (PDI), which measures the extent to which chronic pain interferes with daily activities [21]; two) the Beck Depression Index (BDI), which measures the severity of self-reported depressive symptoms [22]; 3) the Pain Cocky Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ), which evaluates how confident patients feel about carry out a diversity of tasks despite their hurting [23]; 4) the Hurting Catastrophizing Calibration (PCS), which measures the extent of catastrophising thoughts and feelings associated with pain [24]; 5) the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK), which is a measure out of pain-related fear of motion or re-injury [25].

Patients at GSTT who did not exercise a PIP attended a "Technology 24-hour interval" instead. This examines patient expectations of treatment with a psychologist, includes information and question and answer sessions given past a physiotherapist and nurse on the stimulator itself and briefly educates on chronic hurting and ways of managing this more effectively. Formal psychological data is non gathered, and CBT-based interventions are not provided.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics has been used to interpret information equally appropriate, and information were presented mean ± standard deviation if non stated otherwise. Wilcoxon signed-rank not-parametric test has been used to compare psychological variables in the modest subgroup of patients who attended the PIP. Significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Twenty-5 patients underwent a trial of ONS between January 2007 and December 2012 (Male/Female person: seven/18; Average historic period: 49 ± 14 years) (Table 1). Just iii patients did not report enough relief during the period of percutaneous stimulation to consider the trial a successful (success charge per unit = 88%), but one patient notwithstanding requested and received a permanent system. Therefore, 23 patients who received a permanent ONS system were included in the post-obit assay (Table 2).

All patients reached one-twelvemonth follow-upwardly, and 14 of them (61%) exceeded two years of follow-upwards (Boilerplate 36 ± 23 months, median 28 months). 10 (43%) subjects underwent at least one surgical revision after an average of eleven ± seven months from permanent implantation, and 90% of the revision surgeries were needed because of problems with leads. Battery replacements were non considered equally surgical revisions, unless bombardment depletion was caused by high lead impedances. 9 patients required at least 1 surgical revision to supplant the stimulating pb because of deportation (iii), high impedances (2), local infection/skin erosion (2) or painful paresthesia (ii). Eight subjects (35%) had their system removed after an average implant time of 30 ± 21 months (range two – 61 months), either for inefficacy (iv/23), infection (one/23) or both (two/23). One patient requested the removal of the system for psychological reasons despite receiving significant benefit from it.

All 25 patients were reviewed by the headache specialists during the telephone interview. Nineteen patients (76%) were diagnosed with refractory chronic migraine (rCM), three (12%) with refractory occipital neuralgia, ane (4%) with refractory chronic cluster headache and 2 (viii%) with other forms of chronic headache (see Table 1). Interestingly, just 7 of the rCM patients were referred with this diagnosis for ONS, while 11/nineteen were wrongly labelled every bit occipital neuralgia and 1/19 as chronic headache refractory to medical handling.

Seventeen patients with a diagnosis of rCM received a permanent ONS system, and all but iii had a successful trial before the implant (84% success rate). Two of the subjects with an unsuccessful trial did not go on to the full implant. Ane patient, confronting medical recommendation, decided to undergo total implantation despite limited benefit from the trial and reported a mild benefit (< 50% relief) after 5 years of follow-up.

Nine subjects (53%) reported meaning hurting relief (> 50% relief in attacks' intensity and/or frequency) after an average follow-up of 40 ± 27 months (range 11–77 months).

In 5/17 (iv of which with sustained hurting relief), migraine attacks originated in the trigeminal nerve distribution, while eleven/17 patients had their original pain in the occipital area and of those, 5 reported significant relief over fourth dimension. Information technology should exist noted that in about patients headache pain radiates in both territories as the migraine attacks progress.

Seven of the eight patients who had their system removed were classified equally rCM. Five were removed for inefficacy (despite a successful initial percutaneous trial), and one for acquired infection not responding to antibody therapy.

3 subjects were classified as refractory occipital neuralgia, with a history of tenderness over the occipital area and temporary pain relief following at least one occipital nervus block with local anaesthetic and/or steroids. All had a successful trial of stimulation and all of them (100%) study meaning relief (well over 50% reduction in severity and frequency) afterward 28, 28 and 31 months of follow/up from the permanent insertion of the ONS system, respectively.

Seven patients (6 rCM and 1 ON) attended a specifically designed, multi-disciplinary, 2-calendar week pre-implant programme (PIP). Attending the programme was associated with improved scores beyond all measured psychological and functional parameters. Statistically significant improvement occurred in the BDI scores, with a hateful decrease of 7.4 (95% CI: two.3 – 12.five), and in the TSK scores, with an average decrease of 8 points (95% CI: two.2 – 13.8). The analysed population was very modest and differences observed between responders and not-responders did not reach statistical significance. However, long-term responders seemed to accept higher values of PCS scores before the PIP than non-responders, and were able to subtract their BDI values during the course more than those who failed ONS treatment.

Discussion

ONS is a promising handling for some refractory chief headaches, but its office needs further definition. We have presented 6 years ONS feel in two European neuromodulation centres closely working every bit twin teams with tertiary headache centres. Our data is consistent with published studies that propose ONS has a place in the management of patients with refractory chronic migraine and with refractory occipital neuralgia - merely that much work needs to exist done to refine patient selection and optimise the treatment. Our analysis has highlighted of import specific areas to focus on in the hereafter clinical and research apply of ONS.

The concept of a multidisciplinary approach to refractory headaches

In lodge to confront the clinical challenge of refractory chronic headaches there is a demand of at least three different specialists to be involved in the option of refractory headaches patients as potential candidate for ONS: a referring headache specialist, a pain physician with expertise in neuromodulation and a psychologist with expertise in chronic pain. The presence of a headache specialist with expertise in ICDH-Ii diagnostic classes must be considered mandatory in future. Many patients included in our analyzed cohort were reclassified when reviewed by a trained headache specialist: just 25% of the patients were correctly labelled every bit CM at the time of the referral, and but 19% of the subjects originally labelled equally occipital neuralgia fulfilled the ICDH-II criteria for this diagnosis. Our results are in line with previous ONS retrospective analysis, where patients reviewed past an headache specialist were often re-coded [26]. As evidenced by the difference between long-term efficacy (53% CM vs 100% ON) and organisation removal rates (7 patients with CM vs 0 with ON) in our serial, correct diagnosis is essential for scientific and economic evaluation of ONS.

Inappropriate use of the words "refractory" and "intractable" might also led healthcare professionals to improperly label patients every bit "refractory" even if they have not been on an appropriate trial of acute treatments or have never been tried on a preventive medication at an adequate doses for a reasonable menses of fourth dimension [9, 15]. Efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA as a preventive treatment of chronic migraine has been shown in the PREEMPT studies [27] and information technology should at present be added to the list of preventive therapies to exist tried before labeling a migraine patient as refractory and offering them invasive treatments. 15 of the patients included in our series had their arrangement implanted before the PREEMPT publication (and therefore did not receive onabotulinumtoxinA treatment), it is possible that some of them might have responded to onabotulinumtoxinA treatment without the need of an ONS implant.

Patients with chronic migraine experience the same complex spectrum of biopsychosocial issues seen in other chronic pain conditions [28, 29]. Anxiety, low, sleep interference, employment interference, relationship interference and decreased physical and social action are important factors in overall morbidity and should be assessed and addressed. The GSTT subgroup in our data who participated in a pre-implant pain management approach (PIP) experienced improvement across all measured psychosocial domains leading to improved quality of life and health outcomes. Notwithstanding, in our series more patients had a successful implant who did not have a PIP (vii/9 vs 3/7), suggesting that while the PIP is efficacious itself, in its current class it may not provide the best training of patients for an implant. The current PIP focuses on encouraging patients to manage their pain and maximise activity and does not focus on patient selection for ONS.

Careful cess of psychosocial domains should atomic number 82 to improved ONS patient selection and outcomes - this is widely observed recognised in other neuromodulation areas [19, 30, 31]. Hurting duration, psychological distress, pain catastrophising, psychiatric conditions including personality disorders, history of abuse, and meaning cognitive deficits are associated with poor outcomes from pain treatments in general [32]. Depression has been identified equally the single almost of import gene predictive of efficacious Spinal Cord Stimulation [33], and other factors including somatization, anxiety, poor coping likewise predict poor response [34]. Reports on ONS to engagement have focussed on technical details and patient outcomes take centred on hurting scores equally a measure of patient benefit [10] and there is an absenteeism of literature looking at patients' psychosocial and physical status and examining outcomes with quality of life measures.

Stimulation trial equally a reliable predictor for long-term success

A successful temporary trial of stimulation has been considered the best predictor of long-term outcome [35] in different groups of chronic hurting patients who are candidates for neuromodulation. However, a positive trial does not guarantee long term success. The two largest, multicenter, prospective trials of spinal string stimulation for the treatment of chronic pain after spine surgery required a positive trial as fundamental inclusion criteria for patients enrollment [36, 37]. Despite an high initial trial to implant ratio (83% in both studies), successful event at one twelvemonth dropped dramatically (55% - 47%) [37, 38].

At that place is no available literature on the power of a percutaneous trial to predict long-term benefit of ONS implant [39]. Subgroup assay of data coming from i big RCT of ONS in CM showed that patients who positively responded during a percutaneous trial before the permanent implant reported a subtract in headache days per calendar month significantly greater than those who failed the trial [16]. Even so, only short term data was published and so we do not know if the successful trial predicted long-term benefit. Moreover, we do not know if a longer menstruation of stimulation in those who failed the trial might have resulted in benefit in the longer term. In our serial of patients, despite an initial trial success charge per unit of 88%, 7/23 systems were removed due to inefficacy, and just nine subjects (53%) with a diagnosis of chronic migraine reported significant pain relief (>50% relief in attacks' intensity and/or frequency) afterwards an average follow-upwardly of 40 months. A retrospective review of ONS in heterogeneous headache patient population has been recently published reporting similar data in terms of trial success rate (89%), system efficacy (56%), and long-term do good in CM patients (42% at an average of 34 months) [forty].

Rarely ONS-induced improvements are axiomatic within days, as the neuromodulatory processes involved are believed to occur slowly in different areas of the whole nociceptive system [10]. The reported do good of a short (seven – 10 days) percutaneous trial might correspond a placebo effect in a cohort of subjects who ordinarily have unrealistic expectations on the surgery, after having failed most of the available treatments. The view of the International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee is that the subjective nature of migraine features and a high placebo effect invalidate open and unmarried- blind trials of any prophylactic intervention and that the number of migraine attacks and number of migraine days should be collected prospectively for an interval of time long plenty to exist compared with a prospective baseline of at least one month [41]. A ane or two weeks percutaneous ONS trial will not satisfy this standard. Furthermore, when a i-month, semi-permanent, tunnelled trial was employed to test ONS system efficacy before implantation, the long-term effect in CM patients was withal only 47%, despite an accurate evaluation of trial outcomes through specific pain questionnaires [26].

Therefore, the employ of a trial test of ONS is now highly questionable. Its ability to select long-term responders appears poor and with >lxxx% of patients going on to full implantation anyway, a trial poses boosted risk and inconvenience for patients and an economical burden to the wellness intendance system.

Long-term handling efficacy

Neuromodulation is an invasive and expensive treatment, and should exist reserved for specific subset of chronic pain patients following evidence-based guidelines [42]. 350 patients have been enrolled in 3 big, industry sponsored, randomized control trials in the efforts to evaluate safety and efficacy of ONS to treat rCM [12, 13, 16]. 2 found no significant support for an adequate therapeutic effect (responders defined as 50% reduction in headache days per month), and the other establish only a moderate do good (responders defined as 30% improvement in pain) in 39% of the treated subjects. Different written report designs, with controversial end-point choices, exercise not let a directly comparison of the trials' results. Furthermore, no conclusions on long-term treatment efficacy can exist fatigued as just three months follow/upwards data have been reported to date. In our patients the average fourth dimension of system removals for inefficacy is around 23 months (range ii – 54).

An analysis of the available ONS literature reported long-term implant response rate is high (88% to 100%) when peripheral stimulation is performed to elicit paresthesia in the whole painful area, compared to a low response charge per unit (forty%) in those studies reporting non-concordant paresthesia [43]. Some authors hypothesized that the combined stimulation of areas innervated by both the occipital nerves (ON) and supraorbital nerves (SON) might benefit those patients who perceived hurting in a hemicephalic or global extent [43, 44]. Interestingly, in our series we found no differences amid the patients who reported Excellent/Skilful paresthesia in terms of long-term positive outcome (64% vs 66%), and 4 out of 5 patients with migraine origin in the trigeminal area had adept long-term outcome. Moreover two patients had a supraorbital lead added subsequently in the attempt of increment paresthesia coverage and organization efficacy, but only 1 of them reported significant benefit. As adding supraorbital leads increases surgical times and complexity, a carefully designed trial is warranted to constitute the long-term benefit of this new arroyo.

Hardware-related complications

Currently available ONS engineering, originally designed for epidural use, is associated with troublesome complications when used subcutaneously for ONS. Peel erosion, lead breakage, lead migration, and pain around the battery site tin occur. These are not merely direct agin events for the patient, but too bear upon on ONS efficacy, and dramatically increase health care expenditure as further surgical procedures and new equipment are often required. In our series, almost 43% of the patients required at least one surgical revision to treat such problems. In xc% of cases leads or the intermediate connections were the culprit. Similar numbers take been reported in another contempo retrospective review of ONS in heterogeneous headache patient population, with 58% of patients needing a surgical revision [40]. In the larger RCTs, where merely 3 months data have been disclosed, surgical revision rates were already between 19% [13] and 37% [12].

Lead migration and lead breakage, major causes of ONS-related surgical revision, are related to repeated lead and extension traction events due to the high mobility of the implanted area. Over the years, some authors have described techniques to minimize these complications. Bennett suggested securing each lead ipsilaterally to the lateral pocket fascia using 2 suture sleeves separated by a strain relief loop, and anchoring each sleeve to the fascia with 3 sutures and intraluminal medical adhesive [16]. Franzini et al. recommend securing the distal stop of the pb to the lateral portion of the superficial cervical fascia (with two additional skin incisions) to prevent lead migration and report no deportation at i yr follow-upward in 17 patients [45]. Additional strain relief loops are recommended at the upper thoracic level (T2- T4), at the implantable pulse generator (IPG), and at any other incisions [xvi]. Finally, IPG implantation sites other than the traditional gluteal region may accept the reward of less pathway length change during patient movement. Thus, infraclavicular and depression abdomen IPG sites may event in less lead migration/rupture [46]. This literature reveals that specialist expertise by the neuromodulator is important factor in outcome.

Limitations

Our audit has several weaknesses. Its design is flawed by the well-known limitations of retrospective case-series studies [47]. Atomic number 82/anchor technology and our surgical technique have evolved so some of the bug we have highlighted are already beingness addressed. Different measures were collected over the years, and our pick of using patients' subjective study of headache's intensity/frequency reduction to define long-term success is not highly robust. Any prospective trial should now endorse the outcome measures defined past Chore Force of the International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee [41]. Finally, we couldn't collect enough data to report and comment on medication-overuse headache.

Conclusions

Our audited serial of 25 patients treated with ONS in two 3rd neuromodulation centers is consistent with literature suggesting that ONS is a therapeutic option for patients with refractory chronic migraine (9 of 17 patients reporting >50% reduction in headache frequency and or intensity at long-term follow upwards), and refractory occipital neuralgia (all patients reporting >50% reduction in pain frequency and or intensity at long-term follow upwards).

There is a need to refine patient choice for ONS and ensure optimal medical, psychological and surgical management at all stages - a multidisciplinary team comprising of headache, psychology, and neuromodulation specialists is essential for this. Such teams should be used in time to come randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up to further determine the place for ONS in refractory chronic headache management and better patient outcomes.

References

-

Dong Z, Di H, Dai W, et al.: Application of ICHD-2 criteria in a headache dispensary of Mainland china. PLoS One 2012, 7: e50898. ten.1371/journal.pone.0050898

-

Katsarava Z, Kukava M, Mirvelashvili E, et al.: A pilot methodological validation study for a population-based survey of the prevalences of migraine, tension-type headache and chronic daily headache in the land of Georgia. J Headache Pain 2007, 8: 77–82. 10.1007/s10194-007-0367-ten

-

Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Lipton RB: Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Hurting 2003, 106: 81–89. 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00293-8

-

Olesen J, Bousser G-K, Headache Classification Committee, et al.: New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2006, 26: 742–746.

-

Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, et al.: Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American migraine prevalence and prevention study. Headache 2012. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02223.x

-

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Birbeck GL: Migraine: the 7th disabler. J Headache Hurting 2013, xiv: ane. 10.1186/1129-2377-fourteen-ane

-

Wang S-J, Wang P-J, Fuh J-Fifty, et al.: Comparisons of inability, quality of life, and resources employ betwixt chronic and episodic migraineurs: a dispensary-based study in Taiwan. Cephalalgia 2013, 33: 171–181. 10.1177/0333102412468668

-

Lionetto L, Negro A, Palmisani S, et al.: Emerging treatment for chronic migraine and refractory chronic migraine. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2012, 17: 393–406. ten.1517/14728214.2012.709846

-

Goadsby PJ, Schoenen J, Ferrari Doc, et al.: Towards a definition of intractable headache for utilise in clinical practice and trials. Cephalalgia 2006, 26: 1168–1170. ten.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01173.x

-

Magis D, Schoenen J: Advances and challenges in neurostimulation for headaches. Lancet Neurol 2012, 11: 708–719. ten.1016/S1474-4422(12)70139-4

-

Lambru G, Matharu MS: SUNCT and SUNA: medical and surgical treatments. Neurol Sci 2013,34(Suppl 1):75–81.

-

Saper JR, Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, et al.: Occipital nerve stimulation for the treatment of intractable chronic migraine headache: ONSTIM feasibility study. Cephalalgia 2011, 31: 271–285. 10.1177/0333102410381142

-

Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Saper J, et al.: Safety and efficacy of peripheral nerve stimulation of the occipital nerves for the direction of chronic migraine: results from a randomized, multicenter, double-blinded, controlled study. Cephalalgia 2012, 32: 1165–1179. 10.1177/0333102412462642

-

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Nomenclature of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004,24(Suppl 1):nine–160.

-

Schulman EA, Lake AE, Goadsby PJ, et al.: Defining refractory migraine and refractory chronic migraine: proposed criteria from the refractory headache special interest section of the American headache society. Headache 2008, 48: 778–782. ten.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01132.10

-

Lipton R, Goadsby P, Cady R, et al.: P047 - PRISM written report: occipital nerve stimulation for treatment-refractory migraine. Cephalalgia 2009,29(Suppl i):1–166.

-

Linton SJ, Andersson T: Can chronic disability exist prevented? A randomized trial of a cerebral-behavior intervention and ii forms of information for patients with spinal pain. Spine 2000, 25: 2825–2831. 10.1097/00007632-200011010-00017

-

Turk DC, Meichenbaum D, Genest M: Pain and behavioral medicine: A cerebral-behavioral perspective. New York: The Guilford Press; 1987.

-

Turk DC, Okifuji A: Psychological factors in chronic pain: development and revolution. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002, lxx: 678–690.

-

Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al.: Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005, 113: 9–19. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012

-

Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, et al.: The pain disability alphabetize: psychometric and validity information. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987, 68: 438–441.

-

Brook AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri Westward: Comparison of brook depression inventories -IA and -Ii in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Appraise 1996, 67: 588–597. x.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13

-

Nicholas MK: The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Hurting 2007, 11: 153–163. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008

-

Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J: The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Appraise 1995, 7: 524–532.

-

Hudes K: The Tampa scale of kinesiophobia and neck pain, disability and range of motion: a narrative review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2011, 55: 222–232.

-

Paemeleire K, Van Buyten J-P, Van Buynder G, et al.: Phenotype of patients responsive to occipital nervus stimulation for refractory caput pain. Cephalalgia 2010, 30: 662–673.

-

Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al.: OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2010, 50: 921–936. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x

-

Peres MFP, Zukerman E, Young WB, Silberstein SD: Fatigue in chronic migraine patients. Cephalalgia 2002, 22: 720–724. x.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00426.10

-

Pompili Thousand, Serafini G, Di Cosimo D, Dominici Grand, Innamorati M, Lester D, Forte A, Girardi North, De Filippis S, Tatarelli R, Martelletti P: Psychiatric comorbidity and suicide risk in patients with chronic migraine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2010, half-dozen: 81–91.

-

Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Scherstén B: Touch on of chronic hurting on wellness intendance seeking, self intendance, and medication. Results from a population-based Swedish written report. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999, 53: 503–509. 10.1136/jech.53.eight.503

-

Doleys DM: Psychological factors in spinal cord stimulation therapy: brief review and give-and-take. Neurosurg Focus 2006, 21: E1.

-

Tunks ER, Cheat J, Weir R: Epidemiology of chronic pain with psychological comorbidity: prevalence, risk, form, and prognosis. Can J Psychiatry 2008, 53: 224–234.

-

Sparkes E, Raphael JH, Duarte RV, et al.: A systematic literature review of psychological characteristics equally determinants of consequence for spinal cord stimulation therapy. Hurting 2010, 150: 284–289. ten.1016/j.hurting.2010.05.001

-

Celestin J, Edwards RR, Jamison RN: Pretreatment psychosocial variables as predictors of outcomes following lumbar surgery and spinal cord stimulation: a systematic review and literature synthesis. Pain Med 2009, 10: 639–653. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00632.ten

-

Barolat Thou, Ketcik B, He J: Long-term event of spinal string stimulation for chronic hurting management. Neuromodulation 1998, 1: 19–29. x.1111/j.1525-1403.1998.tb00027.x

-

Kumar One thousand, Taylor RS, Jacques L, et al.: Spinal cord stimulation versus conventional medical management for neuropathic pain: a multicentre randomised controlled trial in patients with failed dorsum surgery syndrome. Pain 2007, 132: 179–188. x.1016/j.hurting.2007.07.028

-

Burchiel KJ, Anderson VC, Brown FD, et al.: Prospective, multicenter study of spinal cord stimulation for relief of chronic dorsum and extremity pain. Spine 1996, 21: 2786–2794. 10.1097/00007632-199612010-00015

-

Kumar K, Taylor RS, Jacques Fifty, et al.: The effects of spinal cord stimulation in neuropathic pain are sustained. Neurosurgery 2008, 63: 762–770. ten.1227/01.NEU.0000325731.46702.D9

-

Trentman TL, Zimmerman RS: Occipital nervus stimulation: technical and surgical aspects of implantation. Headache 2008, 48: 319–327. ten.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.01023.x

-

Brewer AC, Trentman TL, Ivancic MG, et al.: Long-term upshot in occipital nerve stimulation patients with medically intractable primary headache disorders. Neuromodulation 2012. ten.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00490.x

-

Tfelt-Hansen P, Pascual J, International Headache Social club Clinical Trials Subcommittee members, et al.: Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: third edition. A guide for investigators. Cephalalgia 2012, 32: 6–38.

-

National Institute of Wellness and Clinical Excellence - Dainty: Spinal cord Stimulation for chronic hurting of neuropathic or ischaemic origin. . Accessed 2 Jul 2012 http://www.nice.org.uk/TA159

-

Reed KL: Peripheral neuromodulation and headaches: history, clinical arroyo, and considerations on underlying mechanisms. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2013, 17: 305.

-

Reed G, Black S, Banta C II, Will K: Combined occipital and supraorbital neurostimulation for the handling of chronic migraine headaches: initial experience. Cephalalgia 2009, 30: 260–271.

-

Franzini A, Messina K, Leone M, Broggi G: Occipital nerve stimulation (ONS). Surgical technique and prevention of late electrode migration. Acta Neurochir 2009, 151: 861–865. x.1007/s00701-009-0372-viii

-

Trentman TL, Mueller JT, Shah DM, et al.: Occipital nerve stimulator lead pathway length changes with volunteer movement: an in vitro study. Hurting Pract 2010, ten: 42–48. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00328.x

-

Hess DR: Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care 2004, 49: 1171–1174.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

SP has received travel reimbursement from Medtronic and Nevro Corp.

AA has received travel sponsorship and speaker fees from Medtronic and Nevro Corp, and he is the principal investigator in carve up studies sponsored past Medtronic and Nevro Corp.

RA has received travel reimbursement from Medtronic and Nevro Corp.

TS has received travel sponsorship and speaker fees from Medtronic and Nevro Corp.

PM has received travel grants from Nevro Corp and St Jude Medical.

AN, EC, VB and GL do not declare any competing interest.

Authors' contributions

SP designed the study, supervised the data collection, performed data analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. AA, RA, TS and SP performed the surgical procedures. AN, GL and PM reviewed patient's notes and diagnosis. VB and EC collect data and took part in information analysis. All authors revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/two.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this commodity

Cite this article

Palmisani, S., Al-Kaisy, A., Arcioni, R. et al. A six year retrospective review of occipital nerve stimulation do - controversies and challenges of an emerging technique for treating refractory headache syndromes. J Headache Pain xiv, 67 (2013). https://doi.org/ten.1186/1129-2377-14-67

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-xiv-67

Keywords

- Headache

- Chronic migraine

- Occipital neuralgia

- Neuromodulation

- Occipital nervus stimulation

Source: https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1129-2377-14-67

0 Response to "what to expect when going for occipital nerve stimulator implantation"

Post a Comment